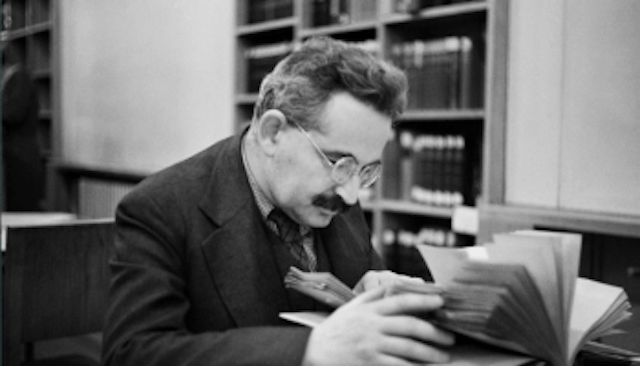

Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), best known for a text called The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction where the world of mass produced artworks, in particular those of photography and film, are explored. Benjamin is also regarded as an iconic intellectual of the twentieth century, who blurred the boundaries of many traditionally isolated subject areas, from the impact of modernity to the meaning of Mickey Mouse. Benjamin was born on 15 July 1892 in Berlin; he was educated at Kaiser Friedrich Schule in Berlin, and at the Landerziehungsheim Haubinda in Thuringia where, significantly, he came into contact with the charismatic school reformer Gustav Wyneken, an important figure in Benjamin’s youth. The German youth movements – via Wyneken’s mediation – inspired Benjamin, and he became a member of the radical ‘group for school reform’ at Albert Ludwig University in Freiburg im Breisgau, also joining the committee of the Free Students Union during his time at the Royal Freidrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. While the youth movements led him to some passionate early publications in journals such as Der Anfang (The Beginning), Benjamin’s academic career did not lead to the expected result of a professorial position: he completed his doctoral dissertation in 1919 (published the following year as The Concept of Criticism in German Romanticism) and worked on his post-doctoral dissertation, or Habilitation, on the German Baroque mourning play, which he completed in 1925, eventually withdrawing it from the University of Frankfurt after an extremely negative reception. The Habilitation called the Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels (The Origin of German Tragic Drama) was eventually published in 1928, alongside a radically different text, the Einbahnstrasse (One Way Street), which is virtually the opposite of a university dissertation, utilizing playful montage techniques and linguistic games.

During this period Benjamin was mixing with exciting new German thinkers, such as his philosopher friends Ernst Bloch and Gershom Scholem (Bloch’s The Spirit of Utopia was published in 1923, the same year as an important new Marxist text, Georg Lukacs’s History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics). Other new intellectual developments were occurring at this time: the German Judaic thinkers Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929) and Martin Buber (1876–1965) were producing challenging works. Buber’s journal, Der Jude, explored literary, critical and political issues of the day, while Rosenzweig published his Star of Redemption in 1921, a book which attempted a ‘new thinking’ bringing together ethics, philosophy and theology; both men worked on a translation of the Hebrew Bible into German, which had a mixed reception. While Benjamin did not ally himself with Zionist thought or a particularly ‘Judaic’ sensibility, he also kept at a distance from other intellectual and cultural movements and charismatic leaders, such as the Georgekreis, a literary and spiritual movement that aimed at a German cultural renewal under the leadership of Stefan Anton George (1868–1933). Benjamin followed an independent path: it took him on complex intellectual and physical journeys, to Paris, Capri, Naples, Rome, Florence, Ibiza, Moscow, Lourdes, Marseille and Port Bou, on the Spanish border, where he committed suicide on 25 September 1940, fleeing Nazi Germany.

During this period Benjamin was mixing with exciting new German thinkers, such as his philosopher friends Ernst Bloch and Gershom Scholem (Bloch’s The Spirit of Utopia was published in 1923, the same year as an important new Marxist text, Georg Lukacs’s History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics). Other new intellectual developments were occurring at this time: the German Judaic thinkers Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929) and Martin Buber (1876–1965) were producing challenging works. Buber’s journal, Der Jude, explored literary, critical and political issues of the day, while Rosenzweig published his Star of Redemption in 1921, a book which attempted a ‘new thinking’ bringing together ethics, philosophy and theology; both men worked on a translation of the Hebrew Bible into German, which had a mixed reception. While Benjamin did not ally himself with Zionist thought or a particularly ‘Judaic’ sensibility, he also kept at a distance from other intellectual and cultural movements and charismatic leaders, such as the Georgekreis, a literary and spiritual movement that aimed at a German cultural renewal under the leadership of Stefan Anton George (1868–1933). Benjamin followed an independent path: it took him on complex intellectual and physical journeys, to Paris, Capri, Naples, Rome, Florence, Ibiza, Moscow, Lourdes, Marseille and Port Bou, on the Spanish border, where he committed suicide on 25 September 1940, fleeing Nazi Germany.

Benjamin’s early writings are deeply metaphysical and theological, and are renowned for their philosophical density. In essays such as ‘On Language as Such and on the Language of Man’ (1916), ‘On the Program of the Coming Philosophy’ (1918) and the substantial ‘The Concept of Criticism in German Romanticism’ (1920), Benjamin presents interlinked concepts of language, sacred text, a projected reworking of Kant’s limited concept of experience, and a new approach to criticism and Romanticism as a tracing of the absolute in early Romantic writing. Benjamin argued for an ‘immanent criticism’ which would engage in some ways quite mystically with a text’s internal structures and divine traces. This very early work can be compared with the popular English translation of Benjamin’s selected essays, collected under the title Illuminations, which show Benjamin theorizing modernity by bringing together, among other things, Marxist dialectics, Surrealism, snippets of theology, Baudelaire’s poetry (and, most importantly, his theories of the flâneur), Kafka’s novels, the image of Proust, a Klee painting called the Angelus Novus, book-collecting, translation, storytelling, photography and film. In this heterogeneous world, old and new collide, the material and the spiritual intersect, industrial modes of production have an impact upon, and transform irrevocably, the making and reception of art, and philosophical grand narratives are broken into small pieces: essays, radio shows, images and fragments.

Illuminations shows how though starting with deep metaphysical and theological perspectives, Benjamin’s thinking was radically modified by his own encounters with Marxism and Surrealism, leading to a hybrid approach to the analysis of contemporary culture. The flâneur – the bourgeois subject strolling idly through the new city-spaces of modernity – is more than a mobile spectator: his very identity is constituted by the physiological charges and shocks of the city, and his enjoyment of the commodification of all subjects. The fast-paced, ever-changing experiences of the city are reflected in new artistic production processes and forms, those of photography and film. Where once the unique high art forms dominated, now, for Benjamin, the mass-produced realm of the copy had come into its own, neutralizing the traditional concepts of individual creativity, genius, eternal value and mystery. Where once the work of art had a unique aura, in part generated by the venerating approach of the subject to the work, fixed in its unique location, now the mass-produced work comes to the subject, meeting her halfway. For example, radio, television and now the internet come directly into the home, and mass-produced works are available and consumed much of the time through ubiquitous advertising. Both ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms are treated by Benjamin as viable objects of collecting and critical study, but new mass-produced works are not secondary to previous forms: the new techniques can achieve things that the old could not, e.g. slow-motion photography or digital images. The ‘copy’ thus outperforms the ‘original’ and does away with this outmoded binary opposition. New technologies of image (re)production de-couple or detach mass-produced art from the sphere of tradition, and from the ritualistic practices in which ‘high’ art is embedded. Instead of achieving significance through sacred ritual, art becomes a political practice. Benjamin adds to this argument his study of history, Marxism and Surrealism, to develop the concept of the ‘dialectical image’ that, as with Surrealist images, substitutes a political for a historical view of the past. Surrealist ‘profane illumination’ is a process whereby all human experiences are revealed to have revolutionary potential: this is revealed via a dialectics of shock, intoxication, the blurring of real and dream worlds, and linguistic experimentation, combined with a radical concept of freedom. Inspired by the ‘profane illumination’, which Benjamin thought exceeded the Surrealist’s grasp, Benjamin went on to develop his ‘dialectical image’ or ‘dialectics at a standstill’ in a massive work of collecting called The Arcades Project. This history of the nineteenth-century Paris arcades, creatively triggered by Louis Aragon’s (1897–1982) Le Paysan de Paris or Paris Peasant (1926), collects thousands of quotations strategically arranged with snippets of critical commentary in chapters or bundles called ‘convolutes’. The materials in each convolute form a critical constellation – or esoteric pattern – whereby the collective dreamworlds of nineteenth-century commodity capitalism are given form and are explosively shattered: the collective can thereby awaken from its non-dialectical slumbers (at least, that is the theory).

Benjamin’s last work – his essay ‘On the Concept of History’ (known previously in English as the ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’) brings together many strands in his oeuvre: a critique of the Enlightenment (and subsequently capitalist) concept of ‘history as progress’, a melancholic analysis of the crisis-bound twentieth century, and the persistence of the theological and the messianic in the midst of the Marxist attempts to develop historical materialism (a rejection of universal truths, and the notion that such truths are teleological, that is to say, moving towards a pre-determined endpoint or goal). For oppressed peoples, Benjamin argues, the ‘state of emergency’ (say, the oppression of a particular ethnic group) is not a lived exception but the rule: adapting this lesson to historical materialism means constantly reassessing the present via past events and emergencies. The past is not something that is hermetically sealed and contained, it must constantly be re-addressed and re-conceptualized as it is dangerously appropriated by the ruling classes at any moment; thus Benjamin argues that: ‘Each age must strive to wrest tradition away from the conformism that is working to overpower it.’ The most infamous image from this final work is the angel in Klee’s Angelus Novus (a painting that Benjamin owned); Benjamin calls this image ‘the angel of history’ and imagines history here as a series of catastrophic events piling wreckage at this angel’s feet as he is blown into the future by the storm that human beings call ‘progress’.

Benjamin is one of the key thinkers of modernity, and an important figure on the margins of the Frankfurt School and other schools of Marxist criticism. While his experimental techniques, and essays on film and popular culture have been the most influential in the West, recent new English translations of a wider range of his work, in particular The Arcades Project, have led to considerable new interest in Benjamin in the English-speaking world. Much of Benjamin’s work is firmly rooted in metaphysics, however, and this aspect of his work continues to be troubling in the post-metaphysical humanities and, in some cases, is simply ignored.

Source: FIFTY KEY LITERARY THEORISTS by Richard J. Lane, Routledge Publication.

Categories: Uncategorized

English Poetry in the Sixteenth Century

English Poetry in the Sixteenth Century  Analysis of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Analysis of John Milton’s Paradise Lost  Join One Year Online Coaching for NTA UGC NET JRF English

Join One Year Online Coaching for NTA UGC NET JRF English  Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock  Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land

Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land  A Brief History of American Novels

A Brief History of American Novels  A Brief History of English Literature

A Brief History of English Literature  Analysis of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s The River Between

Analysis of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s The River Between  Analysis of Miroslav Krleža’s The Return of Philip Latinovicz

Analysis of Miroslav Krleža’s The Return of Philip Latinovicz  Analysis of Rachid Boudjedra’s The Repudiation

Analysis of Rachid Boudjedra’s The Repudiation  Analysis of Euclides da Cunha’s Rebellion in the Backlands

Analysis of Euclides da Cunha’s Rebellion in the Backlands

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.